Significant attention must be given to serious near misses

An effective safety management system will have processes in place that ensure all incidents and near misses are reported and all hazards and at-risk behaviours are identified. Workers in an organization with a strong and thriving safety culture would respond to these systems with active reporting. This is what we want and need to ensure our safety improves. But then we are faced with the reality that this is a lot of information and the old saying “Be careful what you wish for” rattles around in our head. We end up with stacks of incident reports and near misses that have all arrived with the expectation of followup.

Picture this stack of reports, both the reactive and proactive ones, as a pile of ore that has come in from a mine. We know that we need to handle all that ore to find the diamonds that may be present within it. We will need processes and tools and maybe even some intuition to separate out what is of value — the same goes for our safety “ore.”

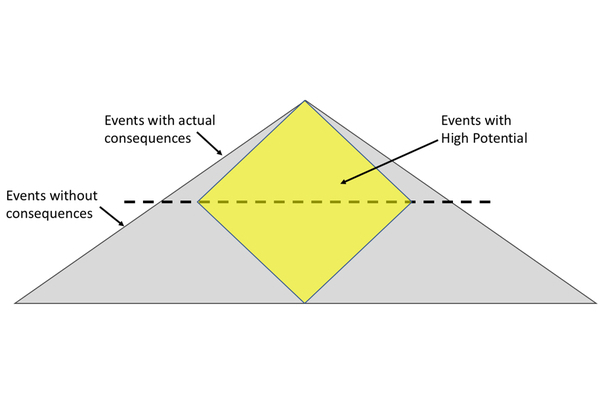

The traditional safety triangle is our pile. It’s a mixture of those incidents with consequences at the top of the triangle and our proactive near misses, hazards and at-risk behaviours at the bottom. A strong safety culture should produce a wide base on that triangle, which means a lot of our data will be from the proactive events and observations. The incidents with consequences will naturally get attention because there has been a loss, damage or injury. These will float to the top of the importance process simply by how we label them — lost-time incident, environmental damage, medical treatment injury, spill, motor vehicle incident, et cetera. Action will be taken based on our investigation’s findings, followup will be expected and our organizations will be asking, “How can we ensure this doesn’t happen again?” We have had an actual event, we know the consequences and we do all we can to prevent recurrence. These fall in the top part of our incident triangle above the consequence line and have an inherent importance.

Incidents without consequences do not always attract the level of attention they should, yet, this may be the really rich ore packed with information that could prevent serious incidents and losses in the future. We need to have processes that help us see the potential outcome of these events under slightly different circumstances. The first step in the process must serve as an efficient screening tool because this will be applied to all the events that are reported. First, we assess what actually happened. Imagine that the following near miss report crosses your desk: “I was on the ground directing the truck as it backed into position. I moved behind the truck from the right side to the left so the driver could see me in his mirror. I tripped on a rut as I was directly behind the truck. The driver continued to back up and I rolled out of the truck’s path.”

The worker wasn’t hurt, the truck wasn’t damaged and the job was completed successfully. When we line up the actual outcome of this event on the incident triangle, we have a near miss that falls below the consequences line. In some safety programs, this would warrant no further action or maybe a token follow-up action, such as remind workers to be careful when acting as a signaller. But this could have easily resulted in a serious injury or fatality. We have found a nugget that needs to be examined in more depth. Why was the worker so close behind the truck? Why did the driver continue moving when he lost sight of his spotter? Were they both trained to the industry standard for hand signals for spotters? Who was supervising this work? Why was it necessary to have workers on the ground where mobile equipment was present? Consider all the questions that would need to be answered if the worst outcome had actually happened and ask them about this event.

There will be some events that need more formal processes beyond just intuition to assess the potential. The following questions can help with the assessment:

How bad could it have been? Near misses that relate to contact with energized equipment, working around mobile equipment, entry into hazardous environments, bypassing safety devices, falls from heights and contact with hazardous agents are usually the ones that will have the high potential. There may be others specific to your work site or industry. Any one of these events could contain that nugget for prevention and improvement.

What were the safety processes that worked? It is important to recognize what prevented the event from escalating to a higher consequence incident. Processes such as the verification of a lockout, activation of a shutdown device, effective use of pre-job planning or precisely following a procedure may have been the barrier that worked.

Which barriers failed and allowed the event to occur? A near miss is an indication that we lost control of something (energy, the equipment, our balance, et cetera) Asking this question will narrow down the point at which we lost control. Multiple failures of processes should attract a lot more attention and examination.

Was it just luck? Events where there are minimal barriers between the actual event and the worst outcome or where luck alone was what prevented the incident demand the most attention. This is a chunk of ore that needs to be put up front and centre and examined by all involved.

A massive pile of safety information will accumulate when you establish a safety culture that is predictive, preventative and forward-looking. There will be some shiny bits of information in that pile that naturally attract attention, but the high-grade nuggets may be hidden within. Processes for mining these diamonds will help you discover the safety mother lode that will make your organization and work site safer.

This article originally appeared in the October/November 2018 issue of COS.